|

Question

The Eng Lang and English team have a question for you which is causing us some consternation, and we would be very grateful if you could help us out. Here is the sentence: The force of gravity on each star is the same and points towards the other star. Our question is: Is this a compound sentence with an implied subject in the second clause (with the subject 'the force of gravity' elipsed in the second clause), OR is this a simple sentence with a compound predicate? Eg as there is no subject here: 'and points towards the other star', technically does this make it a simple sentence? Grammarly and AI tell us that the sentence is simple with a compound predicate, but Sara Thorne (1997) 'Mastering Advanced English Language' says it's a compound sentence. If you have the time to answer and explain the reasoning, we would be very keen to hear from you. (from Judith and the teaching team) Kate's response Many thanks for your wonderful question. It’s caused both Izzy Burke and I to have an interesting conversation over a point of grammar — a rare treat! Certainly, one way of analysing these examples is the following: As you point out, in a compound sentence, there are two (or more) coordinated clauses with overt subjects; e.g.

So something like the following two coordinated imperatives would also form a compound sentence because both clauses can stand alone — the missing subject of the second clause here is of course part of the grammar of imperatives: 2. Do not swill your soup and do not gobble your food. So this account of compound sentences would then force us to recognise another category, the compound predicate that has two (or more) verbs sharing one subject; e.g. 3. Fred swills his soup and gobbles his food. It’s interesting that neither Izzy nor I have ever used this label compound predicate before, and (as far as we can tell) there’s no linguistic textbook that does either, at least none of the usual suspects (though references to “compound predicate” abound on the internet). This would account for Sara Thorne’s analysis. As you know, coordinators always allow ellipsis of the subject of the clause they introduce if it’s co-referential with that of the preceding linked clause — and this really is the preferred construction (from the view point of information flow). And if the subjects and the auxiliaries are identical, ellipsis of both is normal: 4. Fred has swilled his soup and (Fred has) gobbled his food. And let’s not go into what happens when the object is ellipted: 5. Fred likes (soup), and Mary hates, soup. (Though this might sound a bit contrived!). Anyway, to our minds it does add an extra layer of complexity to view examples involving ellipsis differently — and to introduce another label “compound predicate” to cover examples like: “Fred swills his soup and gobbles his food” (or your example “The force of gravity on each star is the same and [it] points towards the other star”). Fortunately, this kind of detail doesn’t come up in the Study Design. But I’m glad you raised it — it’s something that Izzy and I didn’t think of when we put together Chapter 5 in the textbooks. Thank you for contacting us, and for giving us the chance to talk grammar! Question

A question from a language enthusiast (not at a school!). When I was 13 (I’m now 76) my then aunty was a senior Catholic nun who taught English literature, grammar and all things associated with English at a private girls’ boarding school in Ballarat East. I recall meeting her and she asked me….”how are you Richard?” to which I responded, “I’m good thanks” and she said “No, you’re well not good” but I don’t recall, precisely the reasoning behind her answer. I seem to recall that “good” somehow relates to my character and “well” relates to my health and that when people ask “how are you” they’re enquiring about your health rather than your character. Do you agree that my recall explains the reason why "well/not well" (or something similar) should be the preferred response? By the way, whenever I have been asked “how are you?” since that time I have always responded with either “I’m well” or “I’m not well. Richard Kate's response Hello Richard, Thanks so much for your question! I remember too getting into trouble for saying “I’m good” (the reply was usually something like “I know you’re good, but how is your health?). So your recollection that good relates to character and well to health is spot on. Sometimes I was also told that “I’m good” is ungrammatical — not that this was ever explained. But in fact, grammatically there’s nothing separating good and well in this context. True, in Standard English 'good' is an adjective and 'well' is generally an adverb, but well can also be an adjective when it’s a matter of health, as in something like 'I’m well', and this is because it’s following the linking verb am (a so-called copular verb). But there have been changes around these two expressions and the meaning difference between 'I’m well' and 'I’m good' is now more nuanced. 'I’m well' still places more emphasis on a person’s actual health, but 'I’m good' is usually about a person’s general feeling of well-being, perhaps their mood or state of mind (and this is the point Pam Peters makes in her wonderful Australian English Style Guide).' And there's a stylistic difference too. 'I'm good' is more informal, which is one of the reasons it’s more frequently encountered these days — it fits in with the greater informality of language generally (and of course, the Australian love of informality). The changes to this construction have been interesting — go back far enough and you encounter constructions like 'Oh well is me'! Question

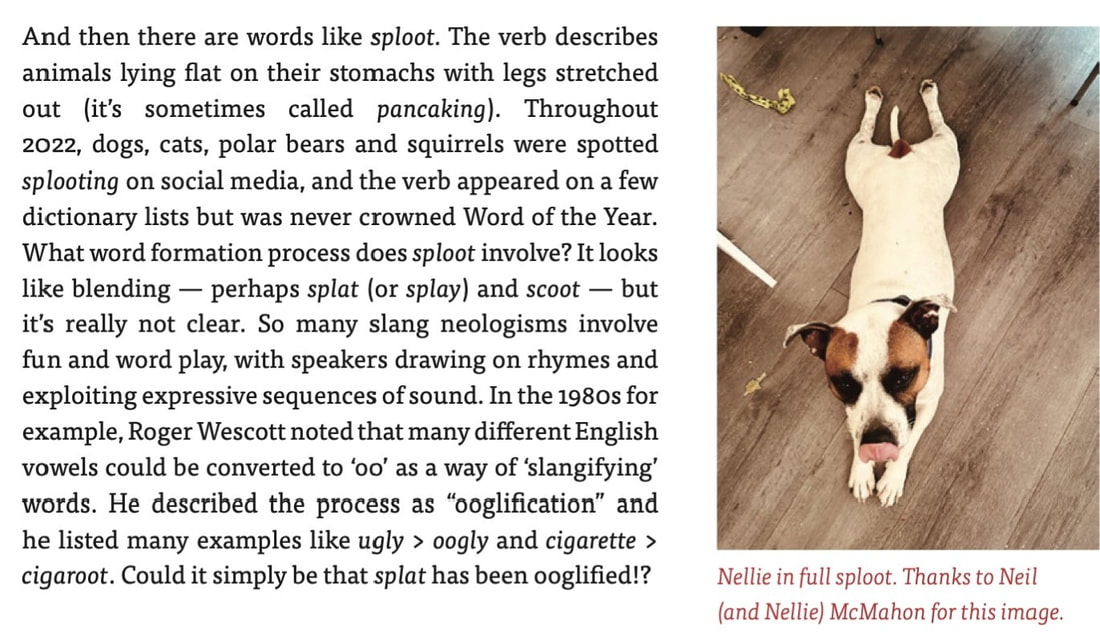

Hi Kate, Deb and Izzy, I now hear the terms “ lucked in” and “ lucked out” being used to mean the same thing. If you get lucky you can be said to have lucked in and also lucked out. I encountered this on the Wordle website when the robot ( bot!) analyses my successful solution. If you have a lucky guess it will say that you lucked out. How can something be both in and out but mean the same? PS I really enjoy your work and love your spot on Sammy J Thanks ,Jon Kate's response Thanks for your question Jon! There’s currently a lot of confusion around 'lucked out'. I use the expression, as you do, with the older meaning ‘be lucky’, but most of my students (and younger speakers generally) understand the opposite meaning ‘be unlucky’. So it's currently a contranym. The driver is probably the expression luck running out (or shit outta luck). But also words to do with luck typically deteriorate — as happened with 'put the mozz on something'. OZ mozz (from Hebrew mazzal ‘luck’) shows a similar shift from ‘luck’ to ‘bad luck’, as in put the mozz on (something) ‘to put a jinx on something’. There is undoubtedly an interesting psychological basis to this sort of deterioration (pessimistic nature of humans?). The expression 'lucked in' is a recent arrival as far as I can tell, and it’s presumably because of the shift in meaning of lucked out. Something similar is currently happening to the gorgeous word doozy. Currently there are two contradictory meanings out there — ‘remarkable, excellent’ and ‘bad’. The negative sense will win out — it always does. Question Can you explain the difference between "pitch" and "intonation" in terms of how VCAA uses them? Because as I was taught, 'intonation' is changes in pitch, whereas pitch relates to how high or low something sounds. But VCAA uses transcript symbols which indicate 'rising pitch' and 'falling pitch' (which sound like changes in pitch, which relate more to the definition of intonation!), and 'continuing intonation', 'final intonation', and 'questioning intonation', which I'm not sure what these exactly mean. (From Jen)  Kate's response That’s a really good question Jen — those terms often get confused (referring for example to the general the highness and lowness of voice). Here are the short definitions we’ve given in the glossary for the Lingo books, and they fit the account you’ve given here: Intonation is the way pitch changes across an utterance. See also intonation contour. Intonation contour is a distinctive sequence of pitches in an utterance. Pitch relates to how high the voice is, reflecting how quickly the vocal cords vibrate. So pitch refers, as you’ve described, to the highness and lowness of tone or voice, and intonation is the distinctive use of pitch patterns in speech (sometimes called melody). Intonation reflects a speech style that’s appropriate to the utterance and the context; for instance, the degree of formality and/or authority. The following example shows a pitch trace (in blue), and you can see that there is an utterance-final “high rising terminal/tune/tone (or HRT)” in the sentence The mentally ill man who burnt down the St Kilda kiosk last year’s been jailed for three years. It’s a speech style that is more likely to resonate with a younger age group (this sentence was read by a female newsreader on a mainstream Melbourne FM radio station — and many thanks to Jenny Price for this example). The various labels this distinctive intonation goes by underscore the confusing terminology here: rising inflection, upspeak, uptalk, high rising intonation, Australian questioning intonation. (And of course HRT is confusing enough!) "A natural progression. Nellie Belle is now immortalised in the academic textbooks -- starring in a new VCE English textbook from Monash's Dept of Linguistics called Love The Lingo, as exhibit A for "splooting"! So proud. She is the first member of her family to go to university." From Neil McMahon, who kindly allowed us to use this image of Nellie splooting in Love the Lingo.

Question

Can you tell me what the origin of “yobbo” is? (Sam, Year 11 student) Kate's response This is a straightforward one. Yob is backslang for boy (with yobbo either extending yob with the -o ending). Backslang, as it’s known, was a secret language once used extensively by barrow boys, hawkers, and traders like greengrocers and butchers (1800s), so they could talk without their customers understanding. “Give her some old bit of scrap” would come out Evig reh emos delo tib fo parcs. Backslang appears in the Detective’s Handbook (1882) — it has a glossary of terms like dab “bad”; delog “gold”; helbat “table”; yad “day”. And yob and yobbo are among the few survivors. Question: One of my students had an excellent question. He wanted to know why we call a building a ‘building’ when it is finished being built. Given the use of -ing to indicate continuing action and verbal nouns, it seems a bit odd that never came up with a different word for a ‘building’ once it is completed.

I was wondering if you have any insights. (Teacher English Language) Kate's response: Great question! The original job description of -ing was to form nouns — at first nouns of action but then during the medieval period the suffix expanded to include a broader range of nouns, and also included things which resulted from the action (like building etc.). It’s interesting that the earlier form in Old English was -ung and the suffix that formed the past participle of veerbs was -ende — somehow these two endings collided to form the -ing we have in the modern language (so two suffixes merged and hence we find today a rather confusing array of functions for -ing). Hope this makes sense! Question In a heated debate with my classmates and teacher, we were discussing whether or not 'Balloon.' is a sentence. Don't ask how we got there, we tend to get quite off track. I decided to solve the debate I'd email you. Is this a sentence (let's say you see a balloon and state 'Balloon'). (VCE student - Billy) Kate's response

Such a good question. There are some very complex analyses of these kinds of structures (treating them as examples of ellipsis, and reconstructing an underlying verb, for example such as "Look, balloon!"), but I never see much point in these sorts of abstract analyses (seems unhelpful to analyse something like "Exit" in terms of "Here is the exit" or "This is the exit"!). I'd simply call this a ‘sentence fragment’ or ‘clause fragment’. This would put it in the same bucket as other verbless clauses like "What a disaster!" and also verbless directives such as “Careful”!, “Two coffees”, “All aboard”! etc. (But something like your example “Balloon!” is also a little like an interjection, isn't it — so something like “Hell”! “Crumbs”! “Wow”! “Pssst”! “Shhh”! etc.). This isn't terribly satisfactory I know, given the label ‘sentence fragment’ includes a whole heap of constructions that happen to be missing crucial bits and pieces like (normally obligatory) verbs and subjects (and the bête noire of many editors and teachers!). |

Authors

Prof Kate Burridge and Archives

May 2024

Submit your question via the Contact form or by emailing us at: [email protected] |